While ‘Les Cœlacanthes’ football team chase continental glory at AFCON in Morocco, Comorian scientists are searching the depths of their ocean for the country’s most enduring symbol — the coelacanth, a 410-million-year-old survivor that has come to represent national pride, resilience, and identity.

Moroni, Union of the Comoros – December 2025. Known locally as Gombessa, the Coelacanth was considered extinct, until rediscovered off South Africa in 1938, with a second specimen found in Comoros in 1952, rewriting biology textbooks and placing the small island nation at the centre of one of science’s most extraordinary stories. Today, Comoros remains one of only four known global habitats for the coelacanth, a species that has become both a symbol of biodiversity – a living fossil – and a powerful marker of national identity.

That identity will be on full display this December, as Les Cœlacanthes, Comoros’ national football team, prepares for its second-ever appearance at the Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) – and the honour of opening the tournament against hosts and overall favourites Morocco on 21 December. For a nation of fewer than one million people, anticipation is building. In the capital Moroni, murals, statues, and street art celebrate the iconic fish that gives the team its name as they prepare to challenge for glory at Africa’s premier football tournament.

A species that has become both a symbol of biodiversity - a living fossil - and a powerful marker of national identity

The symbolism runs deep. Once hidden in the depths, the coelacanth’s survival against the odds mirrors the rise of a national team that has repeatedly defied expectations on the pitch.

“The coelacanth is a symbol of unity and solidarity,” said Ait Ahmed Mohamed Djalim, President of the Les Cœlacanthes Supporters Union. “Comorians from Grande Comore, Anjouan, Mohéli , everyone finds themselves in this symbol.”

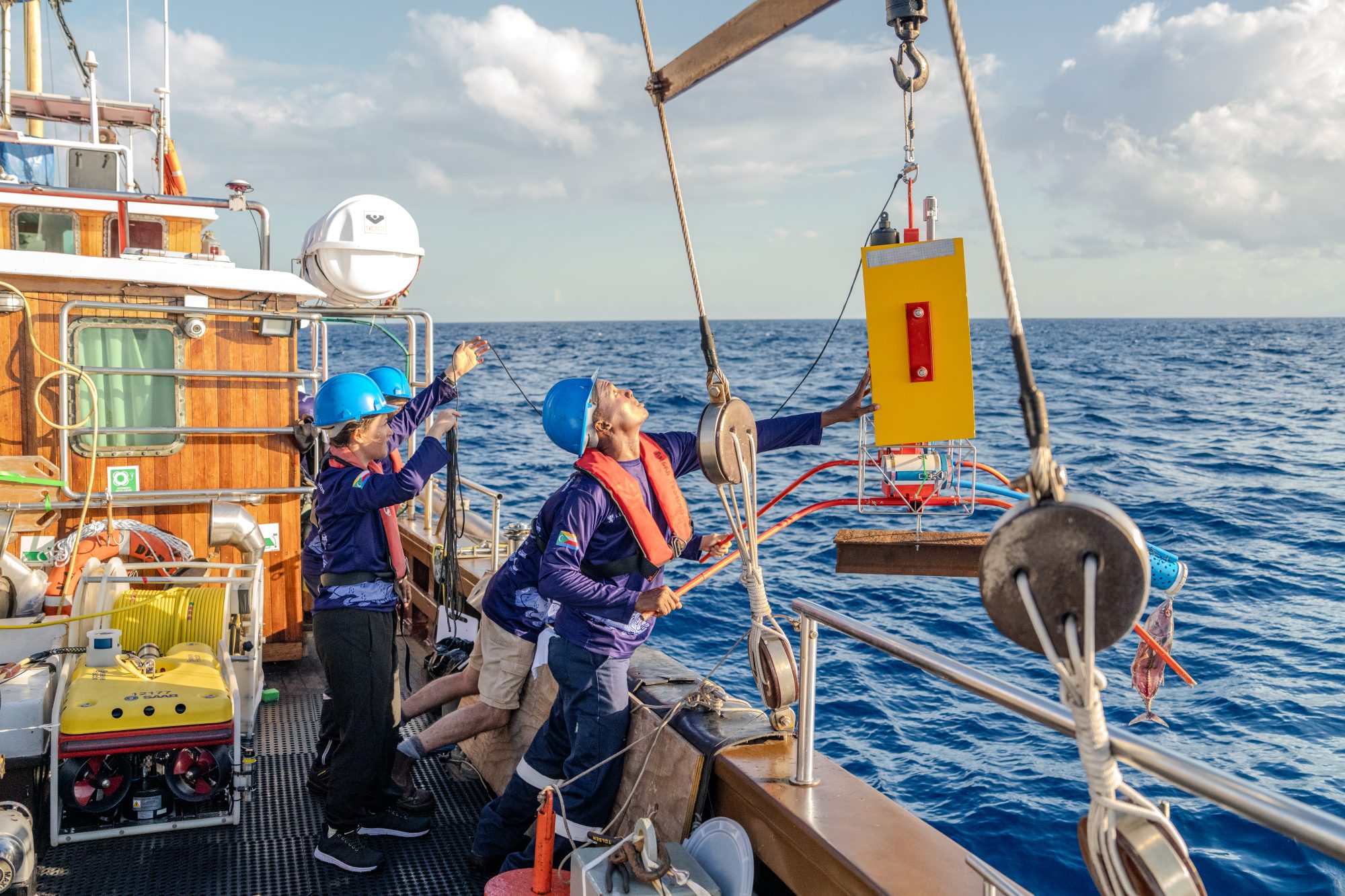

While the players prepare for their toughest challenge yet on the field, scientists are working just as intensely below the surface. Through the First Descent: Comoros mission, the Government of the Comoros and Nekton, working with WILDTRUST under the R-POC programme from October 6th to November 14th, have completed the nation’s first systematic exploration of its ocean (from the surface to 900 metres) in one of the most biodiverse yet least studied regions of the global ocean.

Co-led by Dr Nadjim Ahmed Mohamed of the University of the Comoros, and supported by 17 Comorian researchers, the mission has documented previously unexplored marine habitats while establishing the first Comorian-led research programme dedicated to the coelacanth, a landmark step toward long-term national stewardship of the species.

While the players prepare for their toughest challenge yet on the field, scientists are working just as intensely below the surface

The programme was designed not as a one-off expedition, but as a legacy – equipping Comorian scientists with the tools, training, and knowledge to continue research long after the mission’s departure. Working alongside Nekton scientists, local teams led by Ben Soudjay, Head of Comoros’ Oceanographic Research and Fisheries Departments, are now building a research pathway fully aligned with national priorities.

As Les Cœlacanthes prepares to face Morocco on the opening night of AFCON, the parallels are unmistakable. “You know you will face big teams sooner or later,” said Hamada Jambay, Comoros National Team Manager. “Meeting them from the beginning, without pressure, allows our players to show who they are — to show that Comoros is a team that is difficult to beat.”

As Les Cœlacanthes prepares to face Morocco on the opening night of AFCON, the parallels are unmistakable

For Jambay, the symbolism of the coelacanth runs even deeper. “The coelacanth is history — years and years of resilience,” he said. “It shows that Comoros will last. Like the fish, we were deep, and little by little we are rising up the table. For a country of less than a million people to be ranked 107th in the world — that is something to be proud of.”

The nation’s players step onto the AFCON stage, and its scientists continue their work more than 150 metres below the surface: Comoros is telling a single story — of endurance, pride, and a future shaped by both culture and science.