Sharks aren’t always a welcome sight in shallow waters—but for a team of Comorian and Nekton scientists, their absence was far more alarming.

Sharks are anchors of a healthy food web, and their absence is often a warning sign of a dysfunctional ecosystem that is under strain. So, when they weren’t spotted in the shallows off the Comorian coast during Nekton’s latest First Descent: Indian Ocean mission—in an area renowned for its biodiversity—scientists wondered what it meant for the health of these waters.

Nestled between Madagascar and the Southeastern African coast are the volcanic islands of the Comorian archipelago. Despite being rich in biodiversity, the Comoros Islands remains one of the least studied parts of the global ocean—making it a natural fit for Nekton’s latest mission with First Descent.

After past missions in the Seychelles and Maldives, Comoros was a natural next step—not only because it’s one of the most biodiverse places on earth, but also because the country is part of the 30×30 pledge—a global target to protect 30% of the world’s ocean by 2030. Today, only about 6% of Comorian waters are protected, and there was previously almost no research conducted beyond recreational diving depths. This mission marked the first coordinated, systematic exploration of the nation’s waters.

“The expedition offers a unique opportunity to explore and showcase the richness of Comoros’ marine and coastal ecosystems,” said Dr. Soulé Hamidou, Dean of the Faculty of Sciences & Technology at the University of Comoros. “It will deepen our understanding of biodiversity and fisheries, produce new inventories and habitat maps, and strengthen the skills of Comorian researchers and students. These efforts will build regional and international collaboration and provide clear recommendations for the sustainable management of our marine resources for future generations.”

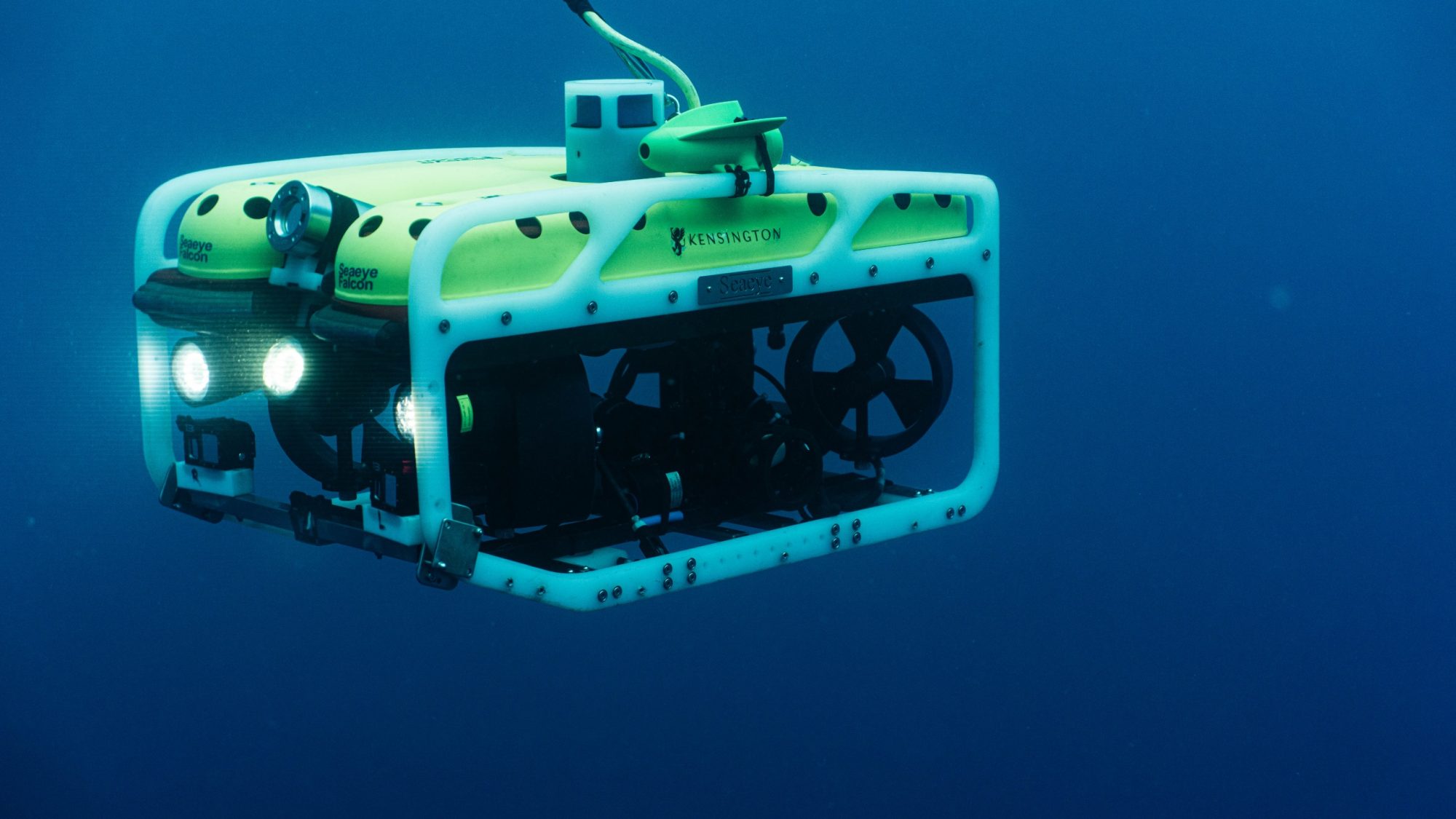

The month-long expedition took place on board the R/V Angra Pequena (“the Angry Penguin”), between October to November 2025. Partners included the Kensington, Government of Comoros, WildTrust, the University of Comoros, CORDIO, and other working under the R-POC program (Renforcement de la Protection des Océans aux Comores – Strengthening Ocean Protection in Comoros)—bringing together Comorian and international expertise to conduct comprehensive marine biodiversity assessments.

“The expedition offers a unique opportunity to explore and showcase the richness of Comoros’ marine and coastal ecosystems”

Protection begins with understanding. Each night, the expedition team used multibeam sonar to generate detailed maps of the seafloor. During the day, they sent baited landers—cameras that rest on the seabed for two hours at a time—and used a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) equipped with high-resolution video and robotic arms to collect biological samples. Repeating this cycle two to three times per day quickly produced a substantial dataset from the surface to 900 meters.

During shallow observations, the team was surprised when they went an entire day without a reef shark sighting. It wasn’t until the following days of deeper dives that they saw sharks, including tiger and thresher sharks at between 100 to 300m and deep-water species such as sixgills between 600 to 900m. Their presence suggests that deeper ecosystems remain relatively intact—a sign of hope amid concerns about overfishing or environmental pressure closer to shore. Sharks maintain healthy ecosystems, indicating sustainable food sources, healthy species populations, and that environmental degradation isn’t too severe. These are the signs that help inform where the Government of Comoros can prioritize marine protected areas (MPAs).

For now, these are only early observations. The expedition produced hours of footage and biological samples that will take months to analyze. These efforts will support the Ocean Census, the largest program in history dedicated to discovering ocean life, launched as a decade-long initiative by Nekton and the Nippon Foundation in 2023. The Ocean Census will also conduct a species discovery workshop with the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity in February 2026.

Shark sightings suggests that deeper ecosystems remain relatively intact—a sign of hope amid concerns about overfishing or environmental pressure

While much of the science happened on board, part of Nekton’s team was stationed on land for much of the expedition, spending time with local organizations and the community. They met with school groups, national park staff, ocean literacy programs, and Comoros’ first independent plastic recycling initiative—started by expats who returned home to tackle plastic pollution on the islands.

Nekton also spent time with local fishers, including the head of the fishermen’s union, to talk about their practices and what they had observed. For communities whose livelihoods depend on the ocean, they recognize the negative impact they’ve had on the waters that they rely on, but they also have ideas on how they can do things better. The fishers spoke candidly about the pressures they face—and came up with their own ideas about how to support a healthier ocean.

For communities whose livelihoods depend on the ocean, they recognize ideas on how they can do things better

Comoros is home to the coelacanth—locally known as the Gombessa—a species once thought to be extinct, with fossil remains dating back 400 million years, that was rediscovered by western scientists in the 1930s. The Gombessa has become a cultural symbol of resilience for Comorians, particularly in the face of climate change. More than a symbol of survival, the Gombessa is considered to have a small but stable population in Comoros. Part of this mission’s objectives involved searching for potential coelacanth habitats, but the real goal was to lay the groundwork for a long-term, Comorian-led research program on this rare species so that they can be stewards of their conservation and care.

The Gombessa has become a cultural symbol of resilience for Comorians, particularly in the face of climate change

Every observation now needs to be verified by data analysis, mapping, and expert review. That process will continue well into next year, leading to open access datasets that can help inform conservation efforts in Comoros and potentially the identification of new species.

Looking further ahead, Nekton will begin to locate future sites for the next First Descent mission. Reliable, long-term funding is essential for this work to continue, and we are very grateful for all the support from the Kensington Cares initiative to accelerate the research that underpins meaningful ocean protection.